The Social Security retirement and Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust funds are approaching insolvency, with both trust funds expected to be depleted in just seven years. Without action, retirees face an automatic 24 percent benefit cut in 2032, while Medicare hospital payments would be cut by 12 percent. Restoring solvency to these trust funds will require slowing benefit growth, lowering health care costs, increasing revenue, or some combination.

The Social Security and Medicare trust funds are financed primarily by a 15.3 percent payroll tax on wages, split evenly between worker and employer, with the 12.4 percent Social Security tax applied only to the first $176,100 of annual wages in 2025. Proposals to boost revenue often involve increasing the tax rate or the tax cap.

This Trust Fund Solutions Initiative white paper suggests a new alternative – replacing the employer side of the payroll tax with a flat Employer Compensation Tax (ECT) on all employer compensation costs.1 While workers would continue to pay payroll taxes, employers would instead pay an ECT on all wages (with no tax cap) and all fringe benefits such as employer-sponsored insurance and stock options.

Karen E. Smith at the Urban Institute modeled this proposal using the DYNASIM model.2 Using that analysis, replacing the employer payroll tax with an ECT would:

Raise $2.5 trillion over a decade and 7 percent of GDP over 75 years.

Close two-thirds of Social Security’s shortfall and half of Medicare’s gap.3

Alternatively, close one-third of Social Security’s shortfall, one-eighth of Medicare’s shortfall, and fund a 1 percentage point cut in payroll taxes – improving solvency while reducing taxes for the bottom 60 percent of workers.

Extend Social Security solvency by two decades to 2055 and modestly extend Medicare solvency – with further extension if combined with other reforms.

Increase progressivity, generating revenue mainly from the highest earners.

Support stronger economic growth than alternative revenue options.

Improve horizontal equity, efficiency, and simplicity; slow health care cost growth; and avoid viability and revenue stability concerns of alternatives.

In combination with other Trust Fund Solutions to reduce costs or increase revenue, an ECT could be a thoughtful, progressive, and efficient way to help put Social Security and Medicare on a sustainable path.

Replacing the Employer Payroll Tax with An Employer Compensation Tax (ECT)

The Social Security and Medicare Hospital Insurance trust funds are financed mainly by a 15.3 percent payroll tax – with 7.65 percent paid by the worker and 7.65 percent matched by the employer. This includes a 12.4 percent Social Security payroll tax (6.2 percent each) on wages up to $176,100 in 2025 and a 2.9 percent Medicare payroll tax (1.45 percent each) on all wages. There is also a 0.9 percent Medicare surtax on worker income above $200,000 (or $250,000 for couples).

Although payroll taxes have few deductions and credits, a meaningful share of compensation remains untaxed by one or both payroll taxes. Wages above the tax cap are not subject to the Social Security payroll tax, while non-wage compensation such as employer-sponsored insurance, employer retirement contributions, and incentive stock options are not subject to either tax nor is this income counted in benefit calculations.

This Trust Fund Solution would replace the 7.65 percent employer-side payroll tax with a new flat Employer Compensation Tax (ECT) imposed on the full cost of all compensation firms pay each year. The worker-side payroll tax and benefit calculations would remain the same as under current law, which are based on wages and up to the current law tax cap for Social Security.

The ECT would apply to all compensation costs, including all wages below and above the current tax cap, employer-sponsored insurance premiums, health savings account contributions, employer retirement contributions, stock options, worker compensation premiums, transportation benefits, and other fringe benefits.

The ECT would be imposed on each employer’s total compensation costs rather than each worker’s pay. Employers would continue to withhold the worker side of the payroll tax based on an individual’s wages, and these wages would continue to be used for benefit calculations.

For this paper, the Urban Institute modelled two ECT options to improve trust fund solvency. A Full ECT that maintains the current combined tax rate of 15.3 percent and uses the revenue for solvency, and a Rate-Cut ECT that uses about half the revenue to reduce the combined tax rate by 1 percentage point to 14.3 percent and the remaining revenue to improve solvency.4

Based on Urban’s modeling, adopting the ECT could also allow a 2-percentage-point rate decrease – to 13.3 percent – on a solvency-neutral basis. Or it could fully restore Social Security and Medicare solvency with roughly a 16.5 percent combined tax rate.

The ECT Could Significantly Improve Trust Fund Solvency

Replacing the employer payroll tax with an ECT would generate substantial revenue and could significantly improve trust fund solvency.

Based on estimates from the Urban Institute, the Full ECT at a 7.65 percent rate would raise $2.5 trillion over a decade. That includes over $2.5 trillion of revenue for Social Security and over $0.2 trillion for Medicare,6 partially offset by nearly $0.3 trillion of income tax losses due to interactions with taxable wages.7 This equals 0.7 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over 75 years – enough to close nearly two-thirds of Social Security’s 75-year solvency gap and nearly half of Medicare’s gap.

Alternatively, the Rate-Cut ECT – which reduces the payroll tax by 1 percentage point – would generate more than $900 billion over a decade, save 0.3 percent of GDP over 75 years, close almost one-third of Social Security’s solvency gap, and close one-eighth of Medicare’s gap.

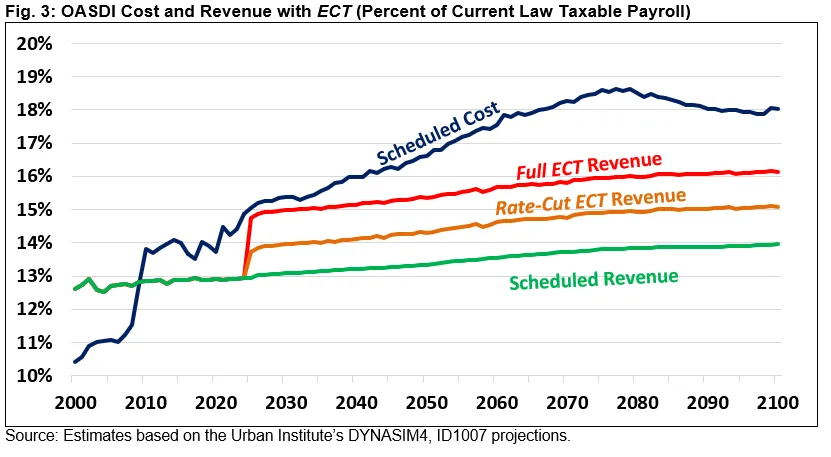

The ECT would accomplish this improvement by significantly increasing the revenue collected to fund both Social Security and Medicare – boosting them by 2.2 percent of taxable payroll and 0.2 percent of payroll, respectively, by 2098.

Under current law, Social Security revenue currently totals about 12.9 percent of taxable payroll (4.70 percent of GDP) and is projected to grow to 14.0 percent of payroll (4.86 percent of GDP) by 2098. Under the Full ECT, Social Security revenue would rise to 16.1 percent of current law payroll (5.62 percent of GDP) by 2098 – closing three-fifths of the 75th year gap. Under the Rate-Cut ECT, Social Security revenue would rise to 15.1 percent of taxable payroll (5.25 percent of GDP) by 2098, closing three-tenths of the 75th year gap.

Meanwhile, the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund revenue currently totals about 3.4 percent of payroll (1.49 percent of GDP) and is projected to grow to 4.6 percent of payroll (1.97 percent of GDP) by 2098. Under the Full ECT, Medicare revenue would rise to 4.8 percent of payroll (2.04 percent of GDP) by 2098. Under the Rate-Cut ECT, revenue would rise above 4.7 percent of payroll (2.00 percent of GDP) by 2098. In both cases (and under current law), revenue in the 75th year would be above costs – but this assumes slow Medicare price growth that the Medicare Trustees, Medicare Chief Actuary, and others have suggested may prove unsustainable.8

The Full ECT would generate enough revenue to delay Social Security insolvency by 20 years to 2055 and to delay HI insolvency by two years to 2037 relative to Urban’s baseline. In combination with other reforms, it could delay insolvency much longer.9 The ECT generates increasing revenue over time due mainly to the expected growth in health care costs. However, Social Security and Medicare costs are also likely to rise over time.

The ECT also provides a more stable revenue source than the employer payroll tax as it is immune to shifts in types and distribution of compensation. Whereas rising health care costs and wage inequality have slowed the growth of payroll tax revenue, they would not affect the ECT.10

The ECT Would Significantly Increase Progressivity

Replacing the employer-side payroll tax with an ECT would significantly increase the progressivity of taxes paid. Although the ECT (like the employer payroll tax) is likely to be borne by workers,11 currently untaxed compensation is skewed toward high-income workers.12

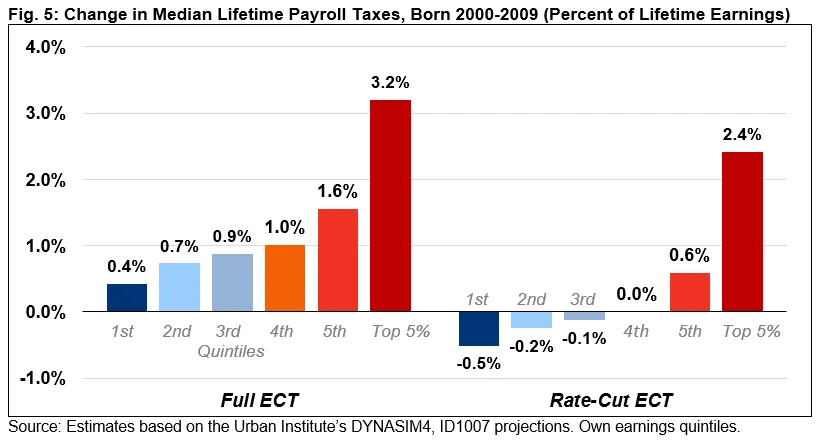

Under the Full ECT, all income groups will pay more in taxes, but those at the top would pay the most by nearly any measure. Under the Rate-Cut ECT, meanwhile, the bottom 60 percent of earners would receive a tax cut; almost all the new revenue would come from the top 5 percent.

According to the Urban Institute, the Full ECT would increase lifetime taxes by 0.4 percent of income for those in the bottom quintile of earners, 0.9 percent for those in the middle, and 1.6 percent for those at the top. Those in the top 5 percent would pay 3.2 percent more.

The Rate-Cut ECT would reduce taxes for the bottom three quintiles, offering a 0.5 percent of earnings cut for the bottom quintile and a 0.1 percent cut for the middle quintile. Those in the top quintile would pay 0.6 percent of earnings more, with the top 5 percent paying 2.4 percent more.

Under the Full ECT, nearly 80 percent of all new taxes paid will come from the top quintile, with nearly 60 percent from the top 5 percent. Under the Rate-Cut ECT, more than all the new revenue would come from the top quintile, with about 95 percent from the top 5 percent. See Appendix II for a more detailed distributional analysis.

Consistent with standard conventions, this analysis assumes the ECT is entirely borne by the worker. Analysis would likely find more progressivity if some of the tax was borne by employers.

The ECT is More Pro-Growth Than Most Alternative Revenue Options

Tax increases generally have mixed and offsetting effects on long-term economic activity – they slow economic growth by reducing incentives to work, save, and/or invest while accelerating economic growth by reducing unified budget deficits.13 The most pro-growth taxes maximize their revenue gains while minimizing disincentives.

Work disincentives can be measured by their impact on effective marginal tax rates (EMTRs) – tax rates paid on the final dollar of earnings.14 The higher the EMTR, the less incentive to work.

The ECT would increase economic growth relative to commonly-discussed options to raise Social Security’s $176,100 tax cap or increase the HI payroll tax rate for high earners.15 The ECT increases EMTRs by less than these options, since it only applies to the employer half of the payroll tax (boosting the top rate by Social Security’s 6.2 percent instead of the full 12.4 percent).

For example, the Full ECT generates similar revenue to eliminating the tax cap, yet its top EMTR is almost 6 percentage points lower for all workers above the current tax cap and is no different for those below the current cap.16

The Rate-Cut ECT generates similar revenue to raising the tax cap to cover 90 percent of wages, but its EMTR is about 6 percentage points lower for a worker making $250,000 and nearly 1 percentage point lower for those below the current tax cap – though EMTRs would be about 3 points higher for incomes over the updated cap at 90 percent of wages (about $320,000).17

While all versions of the ECT do increase the effective marginal tax rate on fringe benefits, those benefits generally tend to be infra-marginal, meaning they often don’t rise directly with additional work. Taxes on these benefits will thus have little effect on the incentive to work.

In addition to encouraging more work, savings, and investment, lower rates leave more capacity for policymakers to raise revenue for other needs, including addressing our mountain of federal debt. The federal revenue-maximizing tax rate is likely between 50 and 65 percent.18 Eliminating the taxable maximum pushes the top EMTR close to 50 percent,19 leaving little room for additional rate increases. By comparison, the ECT leaves the U.S. with more taxing capacity.

The ECT Would Improve Simplicity, Efficiency, Equity, and Viability

In addition to generating more revenue in a more progressive and pro-growth manner, the ECT addresses several other issues with the current payroll tax, including by improving horizontal equity, increasing efficiency, slowing the growth of health care costs, simplifying tax payments for employers, and avoiding several challenges associated with other options.

The ECT improves horizontal equity by taxing similar income in the same way.20 Whereas the current payroll tax effectively favors fringe benefits over wages, the ECT taxes all forms of compensation at the same rate.

This equalized treatment of earnings would make the ECT a more efficient tax, reducing distortions in the current system. Replacing employer payroll taxes with the ECT reduces the incentive to set compensation to minimize tax burden, encouraging employers and employees to instead base compensation on what is best for workers and businesses.

This improvement is particularly important when it comes to the treatment of health insurance. The tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI) encourages employers to offer more compensation in the form of health insurance instead of wages, which is widely understood to contribute to health care cost growth.21 By treating health care benefits the same as other forms of compensation, the ECT is therefore likely to slow health care cost growth.

The ECT only provides a modest haircut to the full ESI tax exclusion, which would be retained for the worker payroll tax and the much larger income tax. Because the ECT applies to the employers who select which insurance plans and benefits to offer employees, it is likely to have a disproportionately significant effect on slowing health care costs relative to its size.

The ECT also simplifies payroll tax payments for employers since they would pay based on their entire compensation cost. For tax purposes, employers would not need to track each worker’s fringe benefit selections and calculate the varying compensation costs for each individual worker.

Finally, the ECT has the benefit of leaving the worker-side payroll tax untouched. As under current law, workers would continue to make annual contributions on the earnings used to calculate benefits. Unlike raising the tax cap, the ECT does not require either offering higher benefits to wealthy seniors or severing the link between worker contributions and benefits.

Unlike broadening the full payroll tax base to cover fringe benefits, the ECT does not require workers to pay taxes on income they don’t directly see in their paycheck – such as income based on the value of health insurance benefits. And unlike most alternatives, the ECT does not directly impose a new tax on workers. Instead, the tax is imposed indirectly through the employer.

Conclusion

With Social Security’s Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund and Medicare’s Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund both just seven years from insolvency, lawmakers must act quickly to avoid abrupt across-the-board cuts in benefits and provider payments. The sooner that Congress acts, the less painful the changes will be and the more opportunity there will be for thoughtful reforms.

Given the short window for action, all options should be on the table. A feasible solution will likely require some combination of slowing benefit growth, lowering health care costs, and generating new revenue – and there are numerous options for achieving each.

The Employer Compensation Tax (ECT) represents a novel approach to fund Social Security and Medicare through a simple, efficient, progressive, pro-growth, and broad-based revenue source in place of the existing employer payroll tax. The ECT could generate enough revenue to close two-thirds of Social Security’s funding gap and half of Medicare’s. Alternatively, it could close one-third of Social Security’s shortfall and one-eighth of Medicare’s while also cutting taxes for the bottom 60 percent of American workers.

The ECT alone would not be sufficient to restore solvency to Social Security and Medicare at the current payroll tax rate. Additional changes to lower health care costs, slow benefit growth, and/or generate further revenue would be necessary. However, the ECT would make a meaningful improvement not only to the trust funds’ finances, but also the way they collect revenue.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget does not endorse any particular solution to restore solvency to Social Security and Medicare. The Employer Compensation Tax (ECT) presented in this paper should be added to the library of potential options lawmakers consider when crafting a broader reform package. The insolvency of the Social Security and Medicare trust funds is less than a decade away, and trust fund solutions are urgently needed.

Appendix I: Questions & Answers on the Employer Compensation Tax

How Would the ECT be Administered?

Nothing would change for workers under the ECT. Worker payroll taxes would continue to be withheld based on wages (up to an annual maximum for Social Security) and remitted to the Treasury, while wage income would continue to be tracked by the Social Security Administration for determining benefits. Instead of effectively paying a matching rate on those taxes, however, employers would pay a single flat tax based on their total compensation costs. Payments would generally be made monthly or semi-weekly as under current law, based on compensation paid (including wages and insurance premiums) over that period. Any fringe benefits not covered by these payments would be paid as part of a company’s annual tax return.

How Would the ECT Apply to Self-Employed Workers?

Under current law, self-employed workers pay both the worker and employer side of the payroll tax through the Self Employment Contributions Act (SECA) tax – generally at a 15.3 percent rate. Under the ECT plan, self-employed workers would pay half their payroll tax rate under the current SECA base and the other half through the ECT. Because most fringe benefits are already taxable (or not deductible) under SECA, the ECT would represent much less of a change for self-employed workers compared to larger employers – the most significant change would be the removal of the tax cap for half of the self-employment tax. One concern with removing the tax cap – even on only half of the payroll tax – is that it could encourage some self-employed workers to reclassify wage income as business income. This could be addressed by reforming “Reasonable Compensation” laws or applying the ECT to all business income of business owners with material participation.22 One option to counteract some of this tax increase for business owners would be to simultaneously narrow the income subject to the SECA half of the tax – for example by making more fringe benefits deductible. Our proposal does not include these reforms.

How Does the ECT Differ from a Value Added Tax (VAT)?

A VAT is a consumption tax imposed at different stages of production. One way to enact a VAT is to impose a business cash-flow tax while removing the deduction for worker compensation. This is known as a subtraction-method VAT.23 An equivalent option is to impose a business cash-flow tax along with an equal-sized tax on worker compensation. In that sense, the ECT does move the employer payroll tax directionally toward a VAT, since it imposes a tax on all worker compensation. However, it does not include business cash-flow income in its base, nor does our proposal integrate the ECT with a business cash-flow tax. Therefore, the ECT is still a tax on income and is not a VAT or other kind of consumption tax.

Does the ECT Raise Taxes on Middle-Class Workers?

The ECT does not impose any direct taxes on workers of any income,24 and adopting the Rate-Cut ECT would actually reduce direct taxes for nearly all workers. At the same time, the ECT would indirectly raise taxes on many households as employers passed the tax along to their workers. Those indirect taxes would be far more efficient than the existing payroll tax, and the majority – 55 to 95 percent – would be paid by those in the top 5 percent of the income spectrum.

Some politicians have said they will not raise taxes on households making below a certain income threshold, such as $400,000 per year. These commitments constrain policymakers from enacting thoughtful tax policy or responsible fiscal policy. Nonetheless, adopting the ECT would not violate this commitment as it is generally structured. Historically, promises not to raise taxes on specific income groups have applied only to direct taxes paid by households, and not to indirect taxes imposed on businesses or other intermediaries.25

Would the ECT Reduce Health Insurance and Retirement Coverage?

The ECT would reduce the tax benefit associated with employer-paid retirement contributions and employer-sponsored health insurance. In doing so, the ECT is likely to slow health care cost growth and also encourage employers to pay workers more in wages relative to health and retirement contributions. However, the ECT would retain most of the tax preference for these and other fringe benefits – including the worker payroll tax exclusion and the income tax exclusion and deferral. This would equalize the treatment of employer and worker retirement contributions. Because the total tax benefit for health and retirement benefits is mostly retained, the ECT is unlikely to substantially reduce the number of employers providing health insurance or employer retirement plans, though it is likely to have some effect at the margin.26

Could the ECT be Applied to the Worker Side of the Payroll Tax?

The ECT is a tax paid by employers only on their total compensation costs. As designed, it would have no impact on worker contributions, which would continue to be paid based on wage income (up to the tax cap in the case of Social Security). Lawmakers could of course choose to also replace the worker payroll tax with a compensation tax – which would effectively repeal the tax cap and all major tax exclusions associated with the current payroll tax. Policymakers would then need to decide whether to pay benefits based on these additional contributions. In “How Much Could Taxing Health Benefits Help Social Security?,” Karen E. Smith and Richard Johnson model a change that moves in this direction by repealing the tax cap and repealing the payroll tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance for both workers and employers. They find this change would boost payroll tax revenue by 31.5 percent, which would be enough to fully restore solvency, assuming no benefits were paid based on these additional taxes (a permanent payroll tax increase of 29 percent in 2025 would achieve solvency). For a variety of reasons, our proposal only applies the ECT on the employer side.

Does Adopting the ECT Come at the Expense of Raising the Tax Cap?

Because the ECT applies to all compensation, it effectively eliminates the tax cap on the employer side. Policymakers could choose to also increase or eliminate the worker-side tax cap. As a rule of thumb, revenue raised from changes to the tax cap would be about half as large if applied after the ECT compared to if applied on top of current law taxes, while the increased costs from paying higher benefits on those higher taxes would be about the same as if applied on top of current law taxes.

Appendix II: Detailed Distributional Results

The ECT represents a progressive change in payroll taxes under any design and by nearly any metric. The table below summarizes various measures of distribution for the ECT based on the DYNASIM model. Estimates are for those born between 2000 and 2009, who are 17 to 26 when the ECT would take effect this year, which means nearly their entire careers would be under the ECT.

Appendix III: Trust Fund Ratios under the ECT

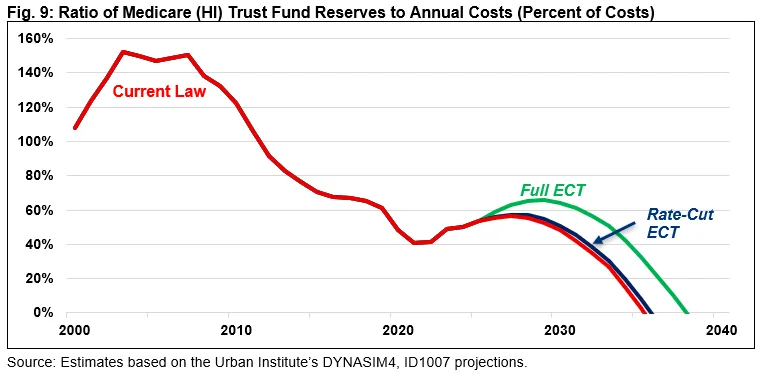

One way to analyze solvency is how the trust fund ratio changes over the 75-year window. The trust fund ratio is the proportion of trust fund reserves relative to one year’s worth of program costs. When the trust fund ratio reaches zero, the trust fund is insolvent.

Under Urban Institute’s baseline, Social Security (OASDI) will be insolvent in 2035. That insolvency date would extend to 2040 under the Rate-Cut ECT and 2055 under the Full ECT.

Under Urban Institute’s baseline, Medicare HI will be insolvent in 2035. That insolvency date would extend to later in 2035 under the Rate-Cut ECT and to 2037 under the Full ECT.

Endnotes

1 The Trust Fund Solutions Initiative is a project of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget to develop and analyze new policy options to help address trust fund solvency and improve the Social Security, Medicare, and highway programs. These options should be considered along with a menu of others. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget does not endorse the options outlined in this paper or in others.

2 The simulations were run on DYNASIM4, ID1007, an Urban Institute projection microsimulation model. It uses surveys and administrative data to project workers through 2100 and aligns to the Social Security Trustees’ report assumptions (although its current law projections are not exactly the same as the Trustees). Urban used federal tax data from the Internal Revenue Service, the National Academy of Social Insurance for worker’s compensation, the Survey of Income Program Participation, and the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation’s PIMS pension model to help them estimate the value of untaxed compensation. Simulations assumed a 2025 start date and used the assumptions of the 2024 Social Security and Medicare Trustees reports. Due to legislative and other reasons, the Trustees now estimate a meaningfully larger funding gap for both programs. We are enormously grateful to Karen E. Smith from the Urban Institute for modeling these options and patiently dealing with our many questions. For more about DYNASIM4, see Cosic, Damir, Richard W. Johnson, and Karen E. Smith, 2024, “Urban’s Dynamic Simulation of Income Model 4.” For more about untaxed compensation, see Smith, Karen E. and Richard W. Johnson, 2025, “Leveraging Tax Data to Measure the Potential Impact of Broadening Social Security’s Revenue Base.”

3 Urban Institute has modelled the Full ECT to close 63 percent of the Social Security 75-year shortfall and 44 percent of the HI shortfall. While Urban modeled most currently-untaxed forms of compensation, they were not able to model all forms of compensation that would be taxed by the ECT. For example, their estimates do not include the effects of applying the ECT to employer-sponsored life and disability insurance or to incentive stock options. In addition, their estimates do not account for some likely shifting of non-taxable compensation to taxable compensation, which would boost revenue from the employee payroll tax. As a result, we expect modestly larger revenue collection than the official Urban estimates, resulting in a slightly larger solvency improvement.

4 Under the Rate-Cut ECT, the combined Social Security tax would be reduced from 12.4 percent to 11.5 percent, and the combined Medicare tax would be reduced from 2.9 percent to 2.8 percent.

5 This excludes a 0.9 percent Medicare surtax on wages above $200,000 for individuals or $250,000 for couples.

6 The Social Security revenue is much larger than for Medicare both because the Social Security tax rate is four times as high as the Medicare rate and because the Medicare payroll tax already applies to earnings above the Social Security tax cap.

7 The Urban Institute estimates this option will reduce federal income tax revenue by $260 billion over a decade because of indirect effects. Actual income tax losses are likely to be somewhat less, to the extent the policy encourages employers to shift from non-taxable to taxable compensation. Nonetheless, any comprehensive Social Security reform plan should be designed or offset in a way that ensures it would not meaningfully add to general fund deficits.

8 Under the law, scheduled provider payment updates for hospitals and other services are reduced by about 1 percentage point per year to account for economy-wide productivity. The Medicare Trustees state “there is substantial uncertainty regarding the adequacy of future Medicare payment rates under current law,” and that by ultimately reducing provider payments below provider costs, provider updates could prove unsustainable. As a result, the Trustees note that “actual future costs for Medicare may exceed the projections shown in this report, possibly by substantial amounts.” Based on input from the 2016-2017 Medicare Technical Review panel, the Medicare Chief Actuary produces an illustrative alternative scenario that assumes the annual update reduction is gradually reduced from 1 percent to 0.4 percent to roughly match private-sector growth. Under this scenario, the HI trust fund faces a 75-year funding shortfall of 1.3 percent of payroll as opposed to 0.4 percent of payroll, and costs significantly exceed revenue throughout the projection window. Relative to this illustrative alternative scenario, the Full ECT would close about 15 percent of the HI funding gap as opposed to 45 percent. Importantly, however, the enactment of the ECT would make current law slightly more sustainable (or less unsustainable) since it would put downward pressure on private health care costs and thus slow the growth in the wedge between private and public payments. By the same token, faster private health care cost growth – in addition to making the current Medicare spending trajectory less sustainable – would increase the revenue raised from the ECT.

9 For example, combining the Full ECT with a cap on Social Security cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) equal to the COLA received by the median beneficiary would delay insolvency for 45 years to 2080. Also adopting the chained CPI for calculating COLAs or indexing the retirement age to longevity would be enough to achieve sustainable solvency for 75 years and beyond. More information on such a COLA cap will be available here.

10 For more on how rising health costs and differential wage growth have eroded the payroll tax base, see: Gary Burtless and Sveta Milusheva, 2013, “Effects of Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Costs on Social Security Taxable Wages;” Kurt Hager, et al., 2024, “Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Premium Cost Growth and Its Association With Earnings Inequality Among US Families;” Xi Li, 2021, “Social Security: Raising or Eliminating the Taxable Earnings Base;” and Rachel West, et al., 2018, “Rising Inequality Is Threatening the Health of Social Security.”

11 Employer-paid payroll taxes are generally assumed to be ultimately borne by workers in the form of lower wages, although some recent research has suggested employers may bear some of the tax. For research and discussion of the incidence of payroll taxes, see: Martin S. Feldstein, 1974, “Tax Incidence in a Growing Economy with Variable Factor Supply”; Richard F. Dye, 1985, “Payroll Tax Effects on Wage Growth”, Jonathan Gruber, 1985, ”The Incidence of Payroll Taxation: Evidence from Chile”; Don Fullerton and Gilbert E. Metcalf, 2002, ”Tax Incidence”; Joint Committee on Taxation, 2013, ”Modeling The Distribution Of Taxes On Business Income”; Emmanuel Saez, Benjamin Schoefer, and David Seim, 2019, “Payroll Taxes, Firm Behavior, and Rent Sharing: Evidence from a Young Workers’ Tax Cut in Sweden”; Dorian Carloni, 2021, “Revisiting the Extent to Which Payroll Taxes Are Passed Through to Employees”; Alex Mengden, Daniel Bunn, 2023, ”The U.S. Tax Burden on Labor, 2023”; and Tax Policy Center, 2024, “How are federal taxes distributed?”.

12 Based on DYNASIM’s estimates and projections, over 90 percent of workers receive some untaxed compensation, and that compensation is highly concentrated at the top. While untaxed compensation represents around 5 percent of compensation for the median worker, it represents about 15 percent for workers at the 90th percentile and is projected to grow to a quarter of their compensation by 2100.

13 Although higher tax rates can reduce the incentive to work and invest, a larger national debt reduces the stock of capital by putting upward pressure on interest rates and “crowding out” private investment. Reducing debt could thus boost private investment and accelerate economic growth. For example, see the CBO, 2024, “How the Expiring Individual Income Tax Provisions in the 2017 Tax Act Affect CBO’s Economic Forecast” showing that allowing the 2017 income tax cuts to expire would shrink output through 2032 but then increase output from 2033 onward as a result of the lower deficits.

14 EMTRs help to explain the financial return for each additional hour or year of work, which workers take into consideration in their labor/leisure trade-off. High EMTRs discourage work, with second earners and those near retirement being especially sensitive. See for example, the CBO working paper by Robert McClelland and Shannon Mok, 2012, “A Review of Recent Research on Labor Supply Elasticities”; CBO, 2012, “How the supply of labor responds to changes in fiscal policy,” Table 1; CBO briefing book, 2019, “Marginal Federal Tax Rates on Labor Income: 1962 to 2028”; Adam Blandin, 2021, “Human Capital And The Social Security Tax Cap,” International Economic Review, 62(4), 1599–1626.

15 Social Security’s Office of the Chief Actuary has scored dozens of proposals that include an increase in the taxable maximum, including the Social Security 2100 Act, the 2010 National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform proposal, and the Social Security Expansion Act, among others. In his Fiscal Year 2025 Budget proposal, President Biden called for increasing the Medicare payroll tax rate from 3.8 percent to 5.0 percent for those with wages over $400,000.

16 Eliminating the taxable maximum without paying any new benefits on the additional taxed wages would close 73 percent of the 75-year shortfall and 56 percent of the shortfall in the 75th year. Raising the taxable maximum to include 90 percent of wages without paying benefits would close 31 percent of the 75-year shortfall and 26 percent of the shortfall in the 75th year. These solvency estimates are based on the 2024 Trustees Report assumptions to match the other solvency projections.

17 Relative to current law, a solvency-neutral ECT would reduce EMTRs by about 2 percent below the tax cap, while increasing them by roughly 3 percent above the cap.

18 Economists Mathias Trabandt and Harald Uhlig estimate a revenue-maximizing rate of 63 percent, while economists Peter Diamond and Emmanuel Saez estimate a revenue-maximizing rate of 73 percent. Subtracting state and local taxes suggests a maximizing rate of about 50 to 65 percent for federal taxes, depending on the location.

19 Currently, a single worker making $1 million faces a federal EMTR of roughly 40 percent; this includes a marginal income tax rate of 37 percent, a 2.35 percent direct Medicare payroll tax, and a 1.45 percent indirect payroll tax paid by the employer, along with some interaction effects. Adding an additional 12.4 percent payroll tax (split between worker and employer) would bring the EMTR to 49.4 percent after considering interactions.

20 For a discussion of concepts of vertical and horizontal tax equity, see Eugene Steuerle, 2002, “And Equal (Tax) Justice for All.”

21 See CBO, 2022, “Reduce Tax Subsidies for Employment-Based Health Insurance”; John F. Cogan, R. Glenn Hubbard and Daniel P. Kessler, 2011, “The Effect of Tax Preferences on Health Spending”; David Powell, 2019, “The Distortionary Effects of the Health Insurance Tax Exclusion”; CRFB, October 2015, “101 Economists to Congress: Keep the Cadillac Tax”; and Jonathan Gruber, 2010, “The Tax Exclusion for Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance,” NBER Working Paper 15766.

22 Owners of S corporations pay Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) payroll taxes as if they were employees of their own firms based on what they define as reasonable compensation based on their material participation in running the business. The compensation is subject to payroll taxes, while the remaining net income is not, which provides a large incentive to minimize reasonable compensation. Reforming reasonable compensation rules would prevent S corporations from misrepresenting income. One option to address this would be to require S corporation owners to pay SECA taxes rather than FICA taxes on reasonable compensation. For more information, see “Tax All Pass-Through Business Owners Under SECA and Impose a Material Participation Standard” in CBO, 2018, “Options for Reducing the Deficit: 2019 to 2028.”

23 For more on the subtraction method VAT, see page 25 of Joint Committee on Taxation, 2016, “Background On Cash-Flow and Consumption-Based Approaches to Taxation.”

24 One possible exception relates to changes to the self-employment tax. To the extent policymakers are worried about the impact of that tax on households below a certain income, they could allow taxpayers below that threshold to continue to pay the full SECA tax while imposing the ECT on income above the threshold. However, this exemption would reduce the solvency impact and introduce some distortions.

25 For example, the Biden Administration proposed nearly $3 trillion of business tax increases (see General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2025 Revenue Proposals) by their own estimates, despite strong evidence that workers bear a portion of these taxes (see Eric Toder, 2025, “The Incidence of the Corporate Tax”).

26 CBO has found that even much more aggressive limitations to the ESI exclusion will only modestly impact coverage. For example, limiting the total income and payroll tax ESI exclusion to the median plan – on the worker and employer side – would increase the uninsured rate in 2032 by less than 0.5 percentage points. See CBO, 2024, “Health Insurance Coverage for the U.S. Population, 2024 to 2034” for more details.