(Illustration by iStock/leremy)

Systemic investing is rapidly emerging as a structural response to the limitations of conventional purpose-driven capital deployment. It is an investment approach that leverages the principles of systems thinking to allocate capital in a way that is highly strategic with respect to a transformative vision; integrated across the capital spectrum; and contextualized in specific places, communities, or supply chains.

Because this is not how purpose-driven finance tends to flow today, it raises the question of how, exactly, systemic investing can be operationalized. Who will generate the systemic intelligence that should underpin funding and investment decisions? Who will convene and coordinate these investment coalitions and translate between coalition members? And who will run learning sessions with coalition members, measure progress, and hold people accountable?

It has long been recognized that changing systems requires systems orchestration. Such orchestration often needs entities to act as the “glue” or connective tissue, and such entities are commonly known as backbone organizations, field catalysts, or network weavers. Usually, backbone organizations convene, coordinate, translate, and advocate. What they typically don’t do is engage investment capital and other sources of finance. Likewise, many purpose-driven capital deployers such as foundations, asset owners, investment managers, impact investors, banks, corporations, and governments understand how to deploy whatever pot of money they control into whatever kind of asset they are mandated to invest in. What they typically don’t do is convene, coordinate, translate, and advocate.

At the intersection of these two worlds—systems orchestration and capital deployment—is a gap. Almost nobody is playing the role of financial backbone to strategically orchestrate diverse sources of financial capital in pursuit of a collective impact mission. As a result, not enough financial capital is flowing in ways conducive to catalyzing systems change.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR’s full archive of content, when you subscribe.

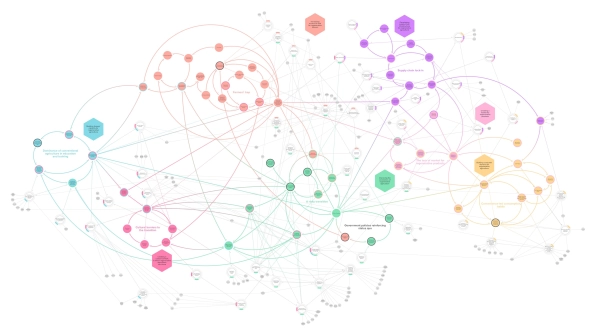

(Click to enlarge)

Figure 1: Financial backbones fill the gap at the intersection of generic systems orchestration and conventional purpose-driven capital deployment (Source: Hofstetter, Gazibara, et al. 2025)

This is why the TransCap Initiative recently convened a group of 29 experts from the fields of investment management, philanthropy, academia, and systems innovation to collectively explore and develop the concept of capital orchestration as a critical function in enabling systems transformation. Between September 2024 and May 2025, we investigated why the strategic coordination of financial capital is not being done routinely as part of ambitious impact initiatives and how a new archetype of financial actor—the financial backbone—could fill that gap. We believe the results of these deliberations, published in a new white paper and discussed below, will help to usher in a new way to think and go about funding systems transformation.

The Need for Capital Orchestration

If we are to achieve an environmentally sustainable and socially just future, we need to fundamentally transform those systems that matter the most for society and the planet: energy, food, mobility, industrial supply chains, cities and the built environment, and landscapes and coastal zones. This kind of transformative change rarely results from a single technology, project, company, or social enterprise. Instead, it tends to emerge from multiple developments occurring within a system simultaneously and with a high degree of shared directionality: new technologies, business models, physical and digital infrastructure, policies and regulations, shifts in social norms and behaviors, innovative educational solutions, and changes in institutional and governance frameworks.

Consider the example of industrial-scale agriculture. Current practices rely on intensive mechanized monocropping, which causes a range of environmental, socioeconomic, and health issues. To transition such systems from their extractive status quo to regenerative and healthy practices requires innovative farming technologies, new supply chain facilities, different lending and insurance products, market-building mechanisms, and technical assistance programs, amongst other things. Importantly, each of these interventions has specific financing requirements. Some are investable with market-rate or concessional investment capital. Others require grants from foundations or subsidies and tax incentives from governments. Still others depend on new insurance products, supply chain finance, income from carbon credits, or advanced market commitments from corporations.

Funding systems transformation thus essentially boils down to a three-pronged orchestration challenge. The first is generating systemic intelligence—figuring out the nature of a societal issue and identifying the financial interventions needed to tackle it. How much capital of what kind and delivered in which way is needed for the transformation of a particular system? For instance, in our work, we observe that a lot of capital in sustainable agriculture flows as venture capital, when some of the most pressing interventions require infrastructure finance or new insurance products.

The second challenge is capital matchmaking—channeling the right kind of capital to the right kind of intervention at the right time. There are several reasons for this. One is the difficulty of assessing how the capital needs of a system change over time, as that system progresses on its transformation journey. For instance, whereas in the beginning of the energy transition the need was greatest for public R&D support and high-risk venture capital, the further build-out of renewable energy now hinges primarily on growth equity and infrastructure finance. Another is pipeline building. There is still a large gap between the investment readiness of many projects and the point at which capital providers prefer engaging in due diligence, requiring the coordination of pipeline maturation, for instance, through the provision of technical assistance. Yet another is that available funding and investment structures are often misaligned with what’s needed. We tend to build what can be financed, rather than what’s necessary. One obvious example is ag tech, which is seen by commercial investors as the easy place to put money, even if often this doesn’t align with the most urgent financing needs in the food system.

The third challenge is creating combinatorial effects—enabling the synergies that arise when two or more interventions are brought into deliberate strategic alignment. For instance, the electrification of transport in a country’s mobility system requires not only that consumers purchase electric vehicles. It also depends on the availability of renewable electricity, power grid capacity, charging infrastructure, insurance products, marketplaces for used cars, and end-of-use vehicle recycling infrastructure. If one of these elements is missing, the system cannot emerge in a holistic form—if, however, all the elements are in place, each makes the others more valuable (and less risky).

All three challenges can only be overcome with a sustained collaborative effort involving multiple types of capital providers and key non-financial stakeholders with a long-term, system-centric capital deployment mandate. This is not how purpose-driven finance operates today. All too often, it is disjointed, moving as standardized venture capital into a startup working on a single-point solution, as project finance to a single piece of physical infrastructure, or as a grant to a nonprofit that does the much-needed work of treating symptoms but has limited ability to address root causes. As a result, standard approaches to purpose-driven finance often fail to catalyze systems transformation.

In the current sustainable finance ecosystem, nobody has a mandate—let alone the capabilities or resources—to coordinate such a collaborative effort. Financial institutions (such as banks, asset managers, pension funds, and family offices) typically focus on deploying capital on behalf of their principals or beneficiaries, not on orchestrating other capital providers interested in the same societal issues. Generic backbone organizations (a.k.a. field catalysts) are experts at systems orchestration, but they rarely have the expertise or compliance infrastructure to engage in investment activities. This is why we need a new archetype of system orchestrator: financial backbones.

The Critical Functionalities of Financial Backbones

A financial backbone is an entity dedicated to strategically mobilizing, coordinating, and deploying financial capital for catalyzing the transformation of systems. It is a new element in the sustainable finance infrastructure, filling a gap between generic systems orchestration and purpose-driven capital deployment. As such, its purpose is to change the way money moves through the system, so that the right kind of capital, in the right amount, flows to the areas with the highest strategic potential to accelerate the desired transition. In pursuit of this purpose, financial backbones perform a wide range of activities, which can be categorized as follows:

Develop, guide, and influence collective vision and strategy: This involves generic orchestration activities, such as stewarding a process to articulate collectively-owned visions and strategies, developing theories of change, and disseminating new knowledge. It also includes a range of activities specific to capital orchestration, such as generating systemic intelligence about capital needs, supporting the construction of strategic investment portfolios, mobilizing capital, and shaping the deal pipeline.Build and nurture long-term strategic partnerships: This includes convening and nurturing multi-stakeholder investment coalitions, building capacity and shaping mindsets, and operating a shared learning and sensemaking infrastructure. It also includes “translating” between different stakeholder groups (e.g., between private-sector investors and governments), building bridges to non-financial system stakeholders such as civil society organizations or community representatives, and facilitating knowledge exchange.Intermediate capital: This comprises structuring and capitalizing new financial instruments (especially where there are critical gaps), playing a matchmaking function between investors and capital seekers, and creating opportunities for innovation and experimentation. It can also include the management of reallocation mechanisms (for example, a fund-of-funds) that channel funding and investment capital from a multitude of sources to existing vehicles and asset managers already active in a system.Support the coalition: This includes designing and maintaining the coalition’s governance structure, measuring and managing its performance and impact, building public support through advocacy and storytelling, and mobilizing resources for coalition members.

Financial backbones are vital—but missing—infrastructure for systems transformation work. Their promise lies in creating the enabling conditions required for collective action amongst capital deployers, such as building trustful relationships, managing information and knowledge flows, creating system awareness, nurturing alignment and coherence, and strengthening a coalition’s resilience and adaptive capacity. Above all, financial backbones generate the opportunity to amplify value (both financial value and impact) and mitigate risks for all stakeholders through the generation of combinatorial effects.

In order to deliver on this promise, financial backbones should adhere to a set of design principles. They should work from the systemic issue outward rather than being driven by the interests or constraints of specific capital holders. They must be endowed with flexibility and adaptive capacity, allowing them to continuously learn and evolve. They should optimize for effectiveness in aligning capital provision closely with the actual capital needs of a system. They should prioritize inclusiveness, participation, and a rebalancing of power dynamics. And they should minimize duplication of effort by building on and amplifying what already exists.

Strategic and Tactical Considerations

Those interested in launching a financial backbone will have to overcome the same well-known hurdles as anyone looking to implement a collective impact initiative: demonstrating to system stakeholders the relevance of orchestration, finding the resources to fund backbone work, and navigating the tensions between taking the time necessary to build trustful relationships while generating tangible value for coalition members quickly. Here is what our work on building a financial backbone for regenerative agriculture in the Midwest, as well as learning from the example of others’ work through our practice community, is teaching us so far.

One challenge is that asset owners and investment managers tend to perceive organizations with capital differently from those that don’t have their own capital. If the financial backbone has agency over a pot of money, it will be seen as a peer and thus taken more seriously than those who don’t have skin in the (investment) game. Having such agency also brings a range of other benefits for a financial backbone’s capital orchestration mission, though it is not without its challenges. Among these are the risks that financial backbones will focus on their own investments at the expense of orchestration work; that they will lose their standing as trusted, selfless facilitators and mediators; and that competitive dynamics with coalition members, especially asset managers, may be introduced.

Another challenge is that capital orchestration takes place in highly regulated and risk-averse environments burdened with complex accountability requirements and bureaucratic procedures. This includes private-sector investors bound by rigorous due diligence and financial compliance standards, government actors restricted by legislated budgets and procurement rules, and foundations governed by committee-based decision making and stringent impact reporting. Further, each of these actors works with its own set of strategic priorities, as expressed, for instance, as “funding verticals” or “target internal rate of return.” Achieving alignment and overcoming organizational constraints makes orchestration a painstaking and slow-moving endeavor.

Orchestration is also perceived as costly, complex, and time-intensive. It’s not that coordination of capital hasn’t been tried, but most efforts tend to boil down to networking and informal alignment. Formalized collective action around capital coordination is still nascent, and the innovation frontier is in finding an operational model that is both effective and simple enough to garner broad buy-in.

Compounding these challenges is the inherently competitive nature of the investment industry. Investors, including impact-oriented ones, are often incentivized to protect proprietary deal flow, differentiate their thesis, and secure outsized returns—dynamics that make collaboration harder. Even when missions overlap, investors may hesitate to share data, co-design blended vehicles, or align underwriting approaches. Then there is the challenge of power and legitimacy. “Orchestrated by whom, and on whose behalf?” is a common question. The challenge for any capital orchestrator is therefore to operate in an inclusive, equitable, and participatory way, overcoming scarcity mindsets and cultural barriers so that it is not perceived as “just another initiative” competing for scarce funding dollars or—from the standpoint of funders—”yet another initiative in a crowded landscape” that runs the risk of being confusing and distracting.

Financial Backbones Have Started to Emerge Organically

Capital orchestration isn’t a futuristic concept. In fact, there are several examples of financial backbones already in existence or being built. An example of the former is the GroundBreak Coalition in Minneapolis-St. Paul. Following the tragic murder of George Floyd in May 2020 and a six-month participatory design process with over 170 community members in 2022, GroundBreak was set up to close racial wealth gaps by supporting BIPOC and low-wealth people to become homeowners and entrepreneurs and to develop commercial real estate. At the heart of the coalition are three GroundBreak-controlled capital pools (one each for low-cost patient capital, grants, and guarantees) designed to crowd-in GroundBreak-aligned loans and equity capital from banks and other private-market capital providers. These capital pools are structured as limited liability companies owned by a 501(c)3 charitable organization and managed by experienced third-party asset managers. GroundBreak operates with a multi-tiered governance structure that includes an executive council representing key coalition partners, strategic impact committees consisting of experts for each impact area, and a project team managing the backbone’s day-to-day activities. GroundBreak is therefore a great example of a financial backbone orchestrating capital in a highly strategic, integrated, and contextualized manner.

An example of a financial backbone in development is the TransCap Initiative’s aforementioned work on regenerative agriculture in the Midwest. This context is particularly fruitful for capital orchestration because many different types of capital deployers are already active within it, but in disjointed and sometimes unstrategic ways. With input from a comprehensive literature review and more than 40 expert interviews, we first generated the analytical basis for understanding what keeps the system in its current state and identifying leverage points for financial capital. Based on this transition map (see Figure 2), we then convened a Design Council of 20 organizations spanning foundations, capital holders, investor coalitions, corporations, farmer representatives, academics, and civil society organizations. This council is currently designing a capital orchestrator for the regenerative agriculture transition in the Midwest, with the intention to move to implementation in early 2026. The team behind this effort is sharing its insights about the process of intentionally designing a purpose-built financial backbone through a series of blogs, which can be followed on their project page.

(Click to enlarge)

Figure 2: Transition map for regenerative agriculture in the Midwest (original Kumu map here).

Closing a Gap in the Infrastructure of Sustainable Finance

Despite these examples, financial backbones remain a rare sight. This is primarily because our collective understanding of the need for capital orchestration is only just forming, so the relevance of financial backbones has been underappreciated to date. As a result, few organizations have a mandate to orchestrate capital, let alone the capabilities or resources to do so. What lies ahead is the challenge of conveying the relevance of this work, particularly amongst foundations, governments, and private-sector asset owners and managers, and then exploring all the different ways financial backbones could manifest in practice.

Financial backbones are a structural response to a structural problem that can be thought of as a new piece of critical infrastructure in purpose-driven finance. If our assumptions hold true, every system transformation effort—from cities implementing climate action plans to corporations seeking to transform their supply chains and philanthropies addressing complex systemic issues—will benefit, or indeed require, someone to play the role of capital orchestrator. One day, financial backbones might be as ubiquitous as banks and foundations.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Dominic Hofstetter & Ivana Gazibara.